On Women’s Inclusion in Repair Culture

An #ASKnet workshop initiative in Rhino Camp refugee settlement, Uganda

In places like the Rhino Camp refugee settlement, there never seems to be a shortage of those willing and able to serve their communities. I interviewed one of the incredible women at the forefront of an amazing knowledge-sharing initiative. Dawa Edina is a South Sudanese refugee in Rhino Camp, Uganda. She is passionate about female empowerment and independence. With a diploma in Information Technology and CISCO Instructor training, she has been encouraging women from her community to learn the skills they will need to independently pursue their goals. Edina led workshops on cyber safety for women and organized the first multi-day event/workshop through CC4D (the Community Creativity For Development) to get women involved in repair culture, and repair from a female perspective. Repair cafes are not only environmentally sound as they decrease the number of things in the trash and new items that need to be produced, but they are also socially beneficial. The cafe empowers those in difficult situations to have agency over their belongings. Independence and community building are products of repair culture, involving women only strengthens these results.

CC4D grew out of the #ASKnet project’s activities. #ASKnet the Access to Skills and Knowledge network is a growing community of grass-roots hubs and local specialists focused on education through already available resources, community expertise and open knowledge sharing. Edina participated in the #ASKnet initiative for the first time in 2018. r0g_ agency for open culture had partnered with CTEN, a local refugee-led organization, to provide open tech and media skills development training. She went on to do the organization’s online training in 2020 as well. The Access to Skills & Knowledge Network is a community working to develop networks that sustainably connect people, addressing the challenges that their communities deal with in the face of conflict and inequality. The network of hubs has a media literacy focus through open knowledge sharing. This catalyzes collaboration, peer-to-peer exchange, and civic engagement, strengthening and creating new opportunities, entrepreneurship, and networks of skills and resources. They desire to facilitate community building through hands-on work and the provision of skills and knowledge training using open access methods. The local resources are utilized to their maximum potential with a focus on the collective expertise of the local people, creating opportunities for mutual support and collaboration (#ASKnet).

In writing this article I also received input from Jaiksana Soro the founder of Platform Africa, He talked about Edina’s outstanding success in the male-dominated IT field and how “she is deconstructing patriarchy in the refugee camp by empowering women.” Edina is an affiliate of the Platform Africa team and helps to lead and advise the organization on promoting the engagement of women in technology. #ASKnet requested that the course participants make suggestions for new programs. Maliamungu Richard, Dawa Edina, and Mathew Lubari were participants in these workshops. They went on to Co-found CC4D with the skills and knowledge they had gained from the workshops. Edina took the initiative and formulated a proposal “Mobile basic ICT training for women and girls.” This first attempt marked the beginning of her journey in learning leadership. Edina worked on the successful “Hardware repair and Tech skills training for youths” program run by her colleague Maliamungu Richard. Edina was disheartened when she saw that only 3 girls were participating in contrast to the 11 boys. Because of her own experience and determination, she took it upon herself to meet with women to find out what changes could make the programs suit their needs.

Edina discovered that this community’s diverse ideas and ambitious initiatives face immense barriers, especially when women are considered. Rhino Camp Uganda with its seven zones and vast land area is difficult to cover for one woman and her team. The most practical problem that the initiatives face remains transportation. There is a truck (Mercedes-Benz 814d) available that can be utilized by the group however the price of fuel (16.85 l/100km) is not the only thing that must be considered. Each time that the truck is to be used the group needs to hire a driver (approx Ugx 175.000/44.95 Euro a day). This is not only a truck but the #Labmobile a mobile maker space. The Labmobile had belonged to a member of the Global Innovation Gathering (GIG), Victoria Wenzelmann; she had converted it into a mobile training space. Jaiksana of Platform Africa saw it at Re:publica, Europe’s largest festival on digital culture and society, and was fascinated by the potential of the Vehicle. Wenzelman donated the van and it has since been equipped with media production equipment and workshop materials to organize workshops in outlying settlements. This Vehicle is essential to women’s empowerment because it removes the barrier of physical distance from their shoulders.

Even when the women took it upon themselves to make it to training far from their home (sometimes up to 2km) their families, husbands, or fathers wouldn’t allow them to go. This problem was exacerbated by the late start times of some of the programs, when they started at 4 or 6 pm women may have faced these journeys in the dark subjecting them to perilous situations. Edina shared an anecdote of one of her repair programs where she spent quite a bit of time convincing the women that they could learn to repair technology and not only attend the sewing classes. Some of the women thought that the hardware repair would be too difficult for them and didn’t come to the training because this intimidated them. Some of the women said that the men were more intelligent and faster learners than them. They were concerned that they would be mocked or ridiculed by the men and wouldn’t be able to learn anything. Suzan, a participant in repair training said she thought repairing machines was for men but that she “came to realize that [she] personally could also do it” This is why a women-specific approach to Repair culture is essential. When there are no or few men present these fears are unnecessary, the women can feel safe to express themselves and ask questions to further their learning. Edina spoke about confidence, and how once the women were convinced to attend their training their courage would grow alongside their knowledge and skills. The women who had participated in the training and were confronted with their intelligence and skills in a field they had been dissuaded from in effect showed them that they could accomplish a lot more than they had believed.

I asked Edina what ideas she had for future projects and she had so much to share. The first thing we discussed was Giving basic ICT (Information and communications technology) foundations to women who have been static in their education and careers. The idea was to give mobile training for an hour in each village and move on to the next one. Because of the aforementioned distance issues bringing the education tools to the women is essential. Women’s empowerment is about agency and freedom. To understand the reasons, any given woman is not succeeding, the intricacies of her situation must be understood. The knowledge brought to women and the things they learn to repair will be relevant to their lives and be flexible to their needs.

In the past repair cafes in the traditional sense have been planned in such a way that has unintentionally been difficult to access for women. Appropriate child care, safety measures, and transportation represent just the beginning when it comes to adjusting these services to the needs of women. It can not be a case of trying to adjust the women to the programs but rather the programs to the women this is something that Edina has intuitively been doing all along. Whether that means bringing the programs to the women or a feminine space like a community church or providing a meal and other such accommodations at an event such as a repair cafe adjustments need to be made to programs so that women feel confident and safe in attendance. So long as a society is not in a place where women and men lead similar lives, equity must be the driving principle to all approaches that wish to work with women. The second idea that Edina and I discussed was the need for more training and time for women to partake in the repair cafes. Skills such as the repair of small technological devices are possible for anyone to learn, but they do need time and encouragement to ensure the knowledge is retained for the long term.

As with any movement, the repair culture phenomenon requires sustainability, Edina and I had different understandings of sustainability. Edina talked a lot about her desire to work with young girls and orphans, doing coding training for kids for example. She wants to train young girls who aren’t in college and ensure their futures. The community aspect of the repair culture is huge in Rhino Camp. A repair cafe is not just a place to acquire valuable skills and get your items fixed, it is, moreover, a location of communal bonding and relationship building.

When a neighbour teaches you how to fix your bicycle you not only regain the use of a transportation method but you are building trust and connection within your community the same can’t be said for purchasing a new bike. Generational knowledge is frequently lost in the wake of conflict and relocation but the sharing of ideas and new information helps to reunite and knit together people again whether the information is new or ancient. The connections it forges between people empower them to collectively grow. Edina’s community connections have supported her in carrying out her past training and will continue to be an asset in the future.

Platform Africa for example considers Edina and CC4D as “ a part of our web of success stories”(Jaiksana). They want to continue to collaborate and support CC4D by sharing resources and assisting them in the field. Because (CC4D) is all about hands-on technology and repair skills, members of their team even run workshops at Platform Africa. My take on sustainability was more literal as a women’s and Gender studies major with an interest in environmentalism. Gender equality, quality education, decent work and economic growth, reduced inequalities, and responsible consumption and production are only a few examples of how Repair culture blends with the Sustainable Development Goals of the UN. Women-oriented Repair culture empowers women in marginalized communities to make more of their own decisions and grants them further agency over their lives. It has been extensively documented that women’s education is essential to any community’s productive progression. For women to attain the same skills and knowledge base, women demonstrate their equal ability to do so and their ability to exercise independence in multiple aspects of life. To find work and to facilitate economic growth communal interconnectivity and future-oriented skill building are essential. People with expertise and the will to succeed exist bountifully within neglected communities and with support can accelerate the growth of their communities in safe and sustainable ways. Reusing and repurposing materials and tools is a necessary part of sustainable development. Maintaining a repair culture and facilitating the knowledge sharing around responsible creation allow communities to flex their growth towards sustainable economic practices and away from late-stage capitalist consumer culture.

Access to knowledge is akin to a human right; one must be able to learn to do the things that the world requires of them. Providing people with open knowledge resources rebukes the idea of intellectual monopoly. When knowledge is borne by a few or few people possess the skills to repair and build, these assets become difficult to access and often commodified. If everyone is to be given an equal chance to grow and succeed the choice to acquire knowledge and skills must be present and encouraged. Repair cafes and other such initiatives build upon and foster community expertise. A sharing knowledge economy. Arguably the most important knowledge resource of our time is the internet. According to the world bank, only 20% of people in Uganda are using the internet, as they are limited in resources such as the funds to pay for it. Uganda has a 12% tax on internet data which can make it an incredible monetary burden, especially on women who tend to have lower incomes. Access to phones and computers is one major way that these numbers could go up. Edina learned to build DIY (do it yourself) solar mobile-phone chargers through the #ASKnet initiative and wants to train women to build them as well. When women can charge their phones in their homes, it is more convenient and much safer than having to go to a public charging station.

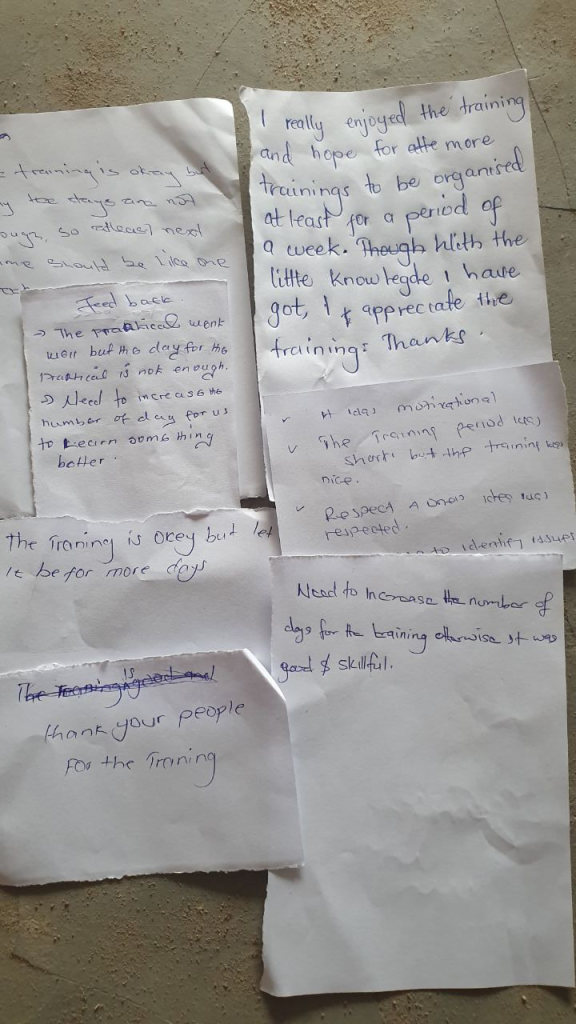

As these initiatives are taking place in a refugee settlement context, it is imperative to discuss their peace-building implications. The achievement of peace is linked to the achievement of stability. Stable access to basic needs and consistent materialization of human rights fulfillment is key. Though necessary, providing equipment and money is not enough to secure a community’s success. Knowledge and skill-building are fundamental to creating interconnected community stability that allows for innovation and collaboration. A repair cafe is a tool that when implemented can encourage the education of individuals, the reinstatement of out-of-commission items and the communal fabric that forges lasting relationships and trust. Skills training and education provide non-violent paths to success (Smith Ellison, 2012). Edina told me that when applying for jobs some employers feel that women aren’t as capable as men “They look at you first as a woman then at your skills”. The women in the training programs were invited to give feedback and some said that the employers frequently seem to express low expectations for women. This sort of attitude works against women but the education they receive builds up this eroded confidence and allows them to prove those people wrong. Edina shared an anecdote of a woman she had trained who had gotten a job through her training. This is essential because the ability to establish independence and livelihood is key to maintaining peace and stability. Attending training, forming a community, and achieving employment help to foster a sense of progress and normalcy. The women whose lives have been uprooted and interrupted sometimes more than once can make up for some of the opportunities and time they have lost with these new education initiatives.

Looking back and moving forward. Women-oriented repair culture is empowering women to achieve independence and gain personal confidence. It is an opportunity to invest in the community and a sustainable future with a reuse-centered economic mindset. Women’s success and peacebuilding go hand in hand. It is imperative to overcome the barriers that women like Edina still have to contend with so that their ambitions can grow and their plans can flourish without hindrance. These aren’t revolutionary ideas but they can revitalize the core of any community. A culture of sharing and mutual benefits is emerging when people approach one another as equals with the intention of rebuilding together.

by Lisa Glock, r0g_agency for open culture and critical transformationBerlin, Germany, July 2022